Craving More Rumaan Alam: A Reader's Entitlement

Alam writes with the keen observational skill of an anthropologist.

“It was this way with men; you had to pretend for it to work.”

I’m not sure if it’s because I read Rumaan Alam’s Entitlement while deeply immersed in work in NYC—surrounded by quintessentially entitled New Yorkers—but this book completely messed with my mind. The characters felt unnervingly familiar. I know these people, and I’m certain you do too. They’re in our workplaces, gyms, social circles, and, without a doubt, all over social media. Maybe you’re one of them. Maybe I am. There’s no shame in that—but it’s crucial to recognize how societal forces shape and mold us into obsessively competitive, consumption-driven individuals, relentlessly chasing more “stuff” and “things.”

Alam writes with the keen observational skill of an anthropologist, capturing the nuances of human behavior with remarkable subtlety and precision. He demonstrated this talent in Leave the World Behind, and in Entitlement, his incisive commentary on class and race takes center stage, further cementing his genius.

Brooke, the protagonist, is the perfect embodiment of what society molds individuals into. In New York especially, you can feel the relentless drive for more—more money, more status, more to flaunt. It’s in the air: a hunger to outdo others and ensure everyone knows it. This energy is palpable, almost tangible. But don’t hate Brooke; hate the society that shapes her.

This phenomenon isn’t exclusive to New York—it thrives in cities like LA, Miami, and London, the financial and consumer capitals of the world. These metropolises serve as playgrounds for influencers and social climbers racing to claim the latest symbol of status, whether it’s a luxury handbag or an elite experience. It’s a chaotic world of endless consumption, where we are consumed by our own desires.

The obsession with having more, with outpacing others, is devouring us. Do you have a house? Do you rent? Do you own? When will you own? But here’s the truth we fail to grasp: all of this owns us. We compare, compete, and measure ourselves against others, losing sight of what truly matters.

Philanthropy Will Not Save Us

My work involves engaging with people in philanthropy—a pursuit I sometimes enjoy, especially thanks to the incredible individuals I’ve had the privilege to connect with. Many of my friends and colleagues passionately believe philanthropy is the key to driving social impact and, ultimately, our collective salvation. Yet, as an economist, I feel obligated to be candid: philanthropy will not save us. In fact, it may be the first to fall short when we need it most.

Brooke’s mother’s candid wisdom encapsulates a hard truth we often ignore: at its core, philanthropy is a sophisticated mechanism for sidestepping the estate tax. It’s not rooted in service, human connection, or the common good—it’s about preserving wealth. It enables the transfer of massive resources from one ultra-rich individual (think Gates or Asher Jaffee) to others, often laden with conditions. Beneath its veneer of generosity, philanthropy upholds systemic inequality rather than dismantling it.

And let’s not kid ourselves: most people in philanthropy aren’t there to challenge the system—they’re drawn to its proximity to power and wealth. Like Brooke, they find ways to convince themselves that they’re making a meaningful impact. But more often, it’s about cultivating their own sense of purpose, relishing their closeness to influence, and basking in the glow of wealth. Brooke herself expects—and feels entitled to—Jaffee “taking care of her.”

This proximity to figures like Gates or Jaffee distorts one’s sense of self. Much like Brooke, individuals become captivated by the power and grandeur of the ultra-wealthy, losing sight of their own values and the larger mission they may have once believed in. Philanthropy, for all its lofty ideals, often seduces its participants into complicity with the very structures they claim to oppose.

Don’t Hate Brooke

It’s easy to hate Brooke. But don’t. Hate the system—the one that creates people like Jaffee and enables them to amass obscene wealth while demanding society look the other way. Brooke is a reflection of what any of us could become in a system that rewards proximity to power and money.

Alam’s brilliance lies in how Brooke views Alissa McDonald, a local Black politician. Brooke sees Alissa as entitled and self-satisfied, even jealous of her ease and familiarity with Jaffee—someone Brooke has only just met. This dynamic is layered and sharp, exposing the fractures within notions of solidarity.

Brooke refuses to see Alissa as a sister, rejecting even the faintest possibility of solidarity. The irony is striking: while Brooke reduces sisterhood to a mere tool—a weapon of leverage—she spares philanthropy from such scrutiny. Instead, she clings to the belief that it holds some inherent virtue, even as it perpetuates systems of inequality. This duality exposes Brooke’s internal contradictions, as well as the pervasive societal forces that pit women, especially across racial lines, against one another.

*

P.S. Has anyone else noticed how often Alam uses the word “demurred”? I’m convinced it’s intentional, and I absolutely love it—because, honestly, is there a better word to capture entitlement? I think not.

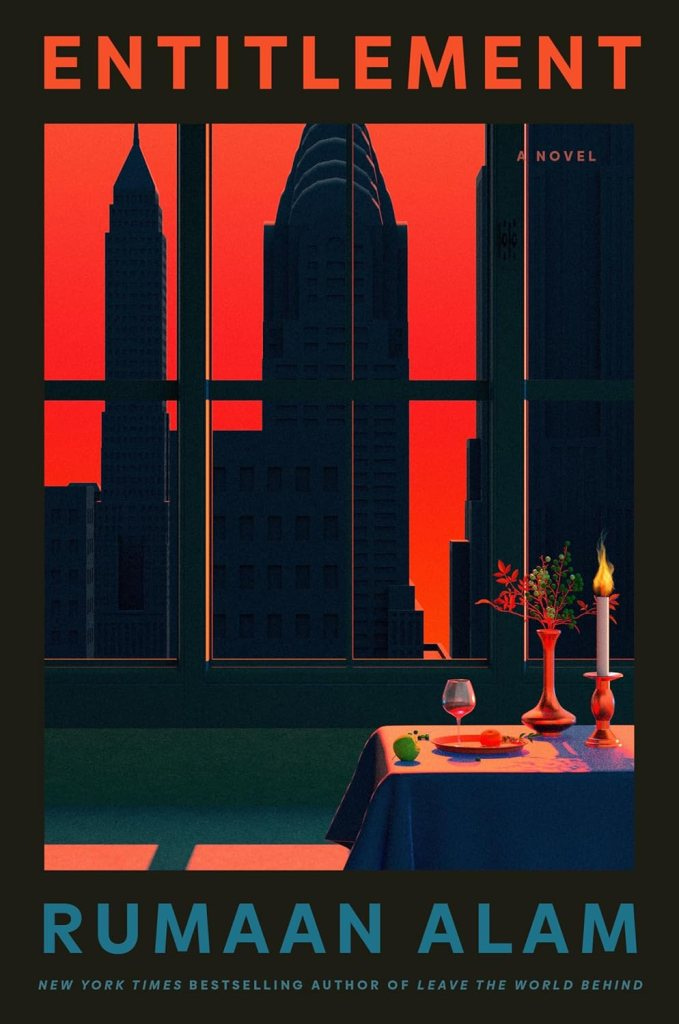

Oh, and did you know the stunning cover art for the novel was created by the incredible Tishk Barzanji? Truly brilliant!