Small Things, Still Burning

When war lingers long enough for death to vanish into the everyday—and no one asks why.

As some of you may already know, I’m a huge fan of Claire Keegan. I’m constantly thinking, writing, and talking about her. She is a wizard. She is a literary genius. Brevity is the soul of her rigor and brilliance. I talk and write about her all the time. I read a Keegan—or two—every year.

Not surprisingly, here I am again talking about Keegan, as I did here:

Keegan, Always Keegan

“Every time the happily married woman went away, she wondered how it would feel to sleep with another man. That weekend she was determined to find out. It was December; she felt a curtain closing on another stage. She wanted to do this before she got too old. She was sure she would be disappointed.”

Last week, I was at Trinity College Dublin to present and deliver three talks to various groups. These talks focused on how we collect and disaggregate data by gender in our budget and data work for the City of Paris. (More on that later—I’ll delve deeper into this topic in a future post.)

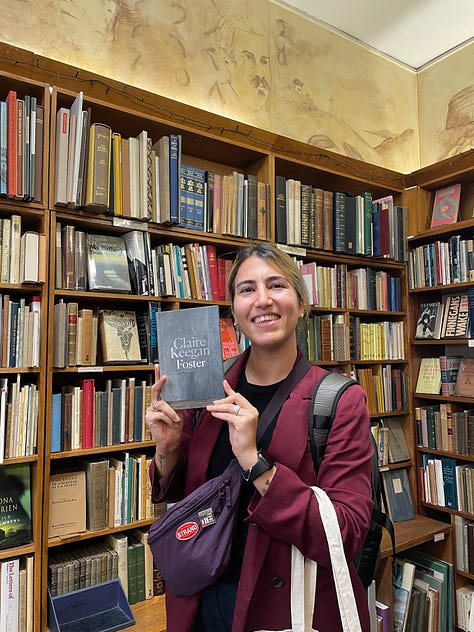

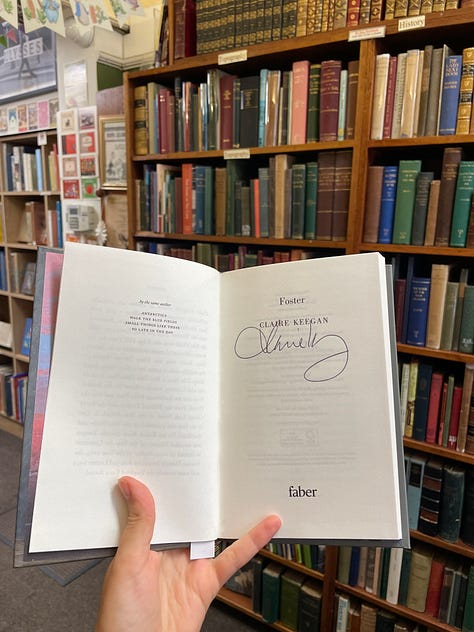

Amidst the endless talks, network chats, and countless cups of coffee, I managed to squeeze in visits to some old bookstores in search of a first edition of Keegan’s work. Hopelessly. Desperately.

Until…

“Many’s the man lost much just because he missed a perfect opportunity to say nothing.”

— Claire Keegan, Foster.

“Eventualities. A good woman can look far down the line and smell what is coming before a man even gets a sniff of it.”

— Claire Keegan, Foster.

Now that we’ve covered me—

that’s not the reason I’m writing this.

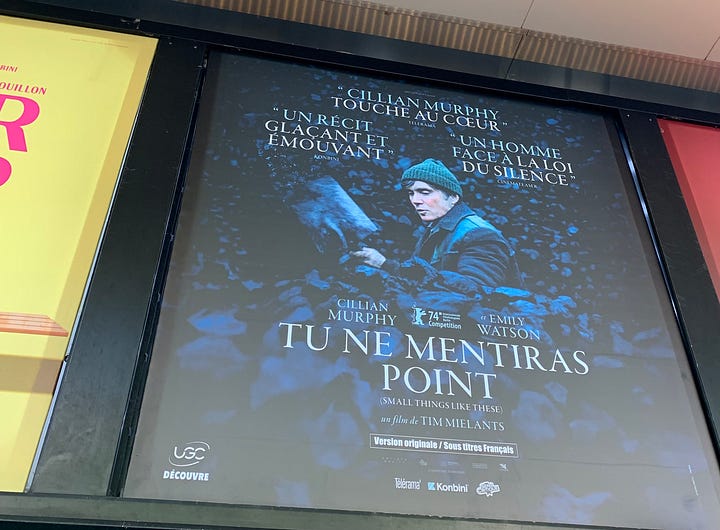

I’m here because today I watched the film Small Things Like These (translated into French as Tu Ne Mentiras Point), directed by Tim Mielants and adapted by Enda Walsh—based, of course, on the novel by Claire Keegan.

“Some nights, Furlong lay there with Eileen, going over small things like these.”

I’ve read this book—I think—four times now. Keegan’s writing is nothing short of extraordinary: sharp, profound, and deeply moving. Though the book feels light in the hand, it leaves a weighty, indelible mark on the heart.

But watching the film—with Cillian Murphy’s hypnotizing performance—on the 589th day of the war between Israel and Palestine lands differently. It hits the body oddly, even violently. It unsettles something that had maybe gone numb.

Of course, the story has nothing to do with war.

But it has everything to do with living alongside atrocity.

With witnessing suffering and carrying on.

With watching a system quietly, efficiently, unleash pain—and watching people absorb it, ignore it, normalize it, just to make it through the day.

The film captures the ache of that—of the inner life that endures in the face of state-sanctioned cruelty, of asking impossible moral questions in a world that rewards silence.

Bill Furlong’s agony—his inner monologue, his quiet, persistent questioning of power—is brilliantly rendered by Murphy. It stings in the context of today. On the 589th day of this war. On any day, really, in an empire that teaches us to pretend all is well.

The empire in Small Things Like These is the Magdalene Laundries and the Irish government.

They are everywhere.

Their grip is everywhere.

They make sure fear is everywhere.

People have a lot to lose—and the system is designed to make sure they do.

Keegan follows Bill Furlong, a Catholic coal merchant, whose modest act of compassion—rooted in his quiet, unwavering moral clarity—takes unimaginable courage. But she’s doing more than telling his story. She’s laying bare the complicity of the Irish state in one of the darkest chapters of its history.

Set in a small Irish town just before Christmas, 1985, the book quietly juxtaposes the rhythms of a working man’s life with the horror of the laundries. These institutions, run by Catholic nuns with full state backing from the 1700s until the 1990s, imprisoned and brutalized women and girls labeled “fallen.” Many had their children taken. Some of those children were sold. Some died. Some were buried in unmarked graves.

In 2014, a mass grave was uncovered in Tuam, County Galway—containing the remains of nearly 800 infants and children discarded in a septic tank.

In the book, Furlong asks a simple, searing question:

“Do you ever question it?”

And his friend, with terror and tenderness, replies:

“Bill, you don’t want to question certain things. Nuns have arms everywhere. Don’t jeopardize your kids’ future.”

Even after multiple readings, one moment in the film shook me differently—perhaps because of the moment we’re in, or maybe because some truths just keep hitting harder with time.

Furlong’s wife says:

“Where does thinking get us? All thinking does is bring you down.

If you want to get on in life there's things in life you have to ignore so that you can keep on.”

And that’s it, isn’t it?

That’s what we do.

That’s what most of us are doing right now.

We ignore what we must to get on.

We convince ourselves that the cost of caring too much is too high.

And I agree with Keegan—

“It seemed both proper and at the same time deeply unfair that so much of life was left to chance.”

Like Bill, I find myself asking:

Is there any point in being alive without helping one another?

And still—

“Always it was the same, Furlong thought; always they carried mechanically on without pause, to the next job at hand.”

We keep carrying on.

We keep moving through the motions, quieting the questions that echo too loudly when we stop.