What Do You Do When You Cannot Leave and Cannot Return?

If you read one memoir in your lifetime, make it Hisham Matar’s “The Return.”

“Had the pain not been so precise

I would have asked

To which of my sorrows should I yield.”— Jaballa Matar, Hisham Matar’s father.

With a quiet dignity, the Libyan writer Hisham Matar reckons with the terrible cost his family paid under Gaddafi’s tyranny.

It has been a long time since a book moved me to tears like this. I’m accustomed to feeling a lump in my throat, pausing to catch my breath, or being momentarily floored by a single sentence—but to find myself utterly unable to hold back tears? That’s rare. The Return, the Pulitzer Prize-winning autobiographical narrative by Libyan-American writer Hisham Matar, shattered me. I don’t think I’ll be able to forget it for a very long time.

Matar’s memoir is a deeply affecting meditation on exile, loss, and the inescapable reach of dictatorship. With a tone both restrained and devastatingly evocative, he recounts his journey to uncover the fate of his father, Jaballa Matar, a prominent Libyan dissident kidnapped and imprisoned by Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in 1990. Though steeped in political history, The Return is, at its core, a story of unbreakable familial bonds, the relentless pursuit of truth, and the enduring weight of hope.

Woven throughout the book are extraordinary acts of resistance by those who, despite living under a regime that “seeps into every aspect of public and private life like a jealous lover,” found ways to remain true to themselves. These moments of quiet defiance underscore the resilience of the human spirit, even in the face of unspeakable oppression.

More than a memoir, The Return reads like a heart-wrenching elegy for all that has been lost. Its subtitle, Fathers, Sons, and the Land in Between, already speaks volumes—it captures the profound displacement of a man who lost his father yet was denied even the knowledge of when and how he was taken. With stunning prose, Matar dissects the meanings of home, memory, ideals, shame, conscience, the invisible threads that bind people to one another, the lingering presence of cities and buildings, power, and violence. Take this sentence, for instance: “To know a book by heart is to carry a home in your chest.” Few writers capture loss with such piercing clarity.

Reading The Return also deepened my understanding of the horrors that unfolded in Libya under Gaddafi—far beyond the superficial knowledge I previously held. Even more unsettling was the chilling resemblance to the authoritarian drift in Turkey today. The parallels are alarming, and Turkey would do well to heed the lessons of Libya’s past. I plan to explore this in a future piece, but for now, the focus remains on Matar’s masterpiece.

There is yet another reason why The Return demands to be read—one that Moroccan author Jordan Elgrably captures eloquently in his article, Why Non-Arabs Should Read Hisham Matar’s ‘The Return’. His argument is both timely and urgent, reinforcing why Matar’s work transcends borders.

“I heard the stories and registered them perhaps the way we all, from within our detailed lives, perceive facts—that is, we do not perceive them at all until they have been repeated countless times and, even then, understand them only partially. So much information is lost that every small loss provokes inexplicable grief. Power must know this. Power must know how fatigued human nature is, and how unready we are to listen, and how willing we are to settle for lies. Power must know that, ultimately, we would rather not know.”

― Hisham Matar, The Return.

A Family Torn by Tyranny

Matar’s father, a fierce opponent of Gaddafi’s rule, was abducted from Cairo and likely perished in the 1996 Abu Salim massacre, where over a thousand prisoners were executed. Yet, the absence of certainty—that small, elusive proof of death—left his family suspended in the torment of the unknown. This profound uncertainty drives Matar’s narrative, shaping his quest to reclaim not only his father’s story but also his own sense of belonging. Born in Libya but raised in exile, Matar’s life has been punctuated by seismic moments of displacement: his family’s departure from Libya in 1979 when he was just eight years old, the horror of his father’s disappearance, and the slow realization that the world’s powers often choose indifference over justice.

Britain: Nothing Good Ever Comes Out of It

The cold machinery of Britain's power played a crucial role in the disappearance and likely death of Matar's father. One of the book’s most chilling moments occurs in the winter of 2010 when Matar, alongside his wife Diana and his brother Ziad, attends a session at the House of Lords in London. There, the human rights advocate Lord Lester questions the British government about Jaballa Matar’s fate. Hearing his father’s name echo through the chamber is a vertiginous experience for Matar, a moment that underlines both the personal and political dimensions of his struggle. Yet, the official response is sterile and detached: Our embassy in Tripoli has raised this with the Libyans and asked them to investigate further, Baroness Kinnock, then a minister of state, replies.

In the same session, Peter Mandelson—known for his ties to Gaddafi’s son, Seif al-Islam—fixes Matar with a cold, expressionless gaze, a moment that encapsulates the hypocrisy of Western diplomacy. The casual cynicism with which British officials handled Libya’s human rights abuses is staggering. David Miliband, then foreign secretary, dismisses Matar’s advocacy as ‘unhelpful noise,’ a remark that starkly reveals the callous pragmatism of political power over human suffering.

Here’s what Matar describes of his interaction with Miliband:

“So tell me,” David Miliband said. “Are you British now?”

“Yes.”

“Good man. Excellent. So you’re one of us.”

Was he patronizing me? Perhaps not. Perhaps it was the genuine warm confederacy of a fellow-Brit. Or, then again, maybe it was the impatient, political, bullying pragmatism of power towards a person of mixed identities, a man whose preoccupations do not fit neatly inside the borders of one country, and so perhaps what Miliband was really saying was,

“Come on, you’re British now; forget about Libya.”

— Hisham Matar, The Return.

For all that he has been through personally, Matar remains clear-eyed about Britain’s entanglement with Gaddafi. He notes that the calamity that followed Gaddafi’s fall was more true to the nature of his dictatorship than to the ideals of the 2011 revolution—just as Britain’s role in Libya’s misfortune can be traced back to Tony Blair’s infamous desert handshake with Gaddafi in 2004. The decisions made in those years, Matar implies, bore fruit long after they were first set in motion.

A Journey of Hope and Heartbreak

Matar’s return to Libya in 2012—accompanied by his mother and wife—frames the book, a pilgrimage that offers both revelations and more agonizing questions. In Benghazi, he meets a man who insists he saw Jaballa Matar alive in 2002 in a prison ominously called the Mouth of Hell. But, when presented with a photograph, the man hesitates, then backtracks: Perhaps it was someone else. For Matar, the pain of ambiguity is almost unbearable. How can the vast universe of a person—their thoughts, longings, fears—be reduced to the uncertainty of a single date on a calendar? The impossibility of closure defines his grief. Unlike those who have lost loved ones with certainty, Matar’s mourning only intensifies over time, his father’s presence growing larger rather than fading into memory.

The Poetry of Sorrow

Despite its harrowing subject matter, The Return is a book of exquisite beauty. Matar’s prose is both restrained and deeply affecting, his descriptions suffused with an aching intimacy. He recalls the tenderness of massaging his father’s feet, the quiet comfort of his mother whispering lines from a smuggled letter, the solace of familial gatherings over sweet tea and pastries. These moments of warmth shine through the darkness, reminding the reader that even in the face of atrocity, love endures.

Unlike many political memoirs, The Return does not seek to be ‘unflinching’—a term critics often use as praise. Instead, Matar flinches constantly, turning away from the abyss of horror. His restraint is what makes his grief so searing, his refusal to sensationalize making the violence all the more unbearable. The image of bloodied watches collected after the Abu Salim massacre is devastating precisely because Matar does not dwell on it. He allows absence, silence, and omission to speak louder than graphic detail.

A Legacy of Dignity

At times, Matar reflects on the anger that once consumed him. But the defining quality of The Return is its gentleness—a quiet, almost miraculous humanity that emerges from unimaginable suffering. One senses that this generosity of spirit is, in part, an inheritance from his father. Matar imagines Jaballa in his final moments, offering solace to his fellow prisoners, standing straight-backed, reciting the Qur’an’s reassurance: With hardship comes ease. With hardship comes ease.

It is with this same dignity that his son now stands, carrying the weight of a loss that has no end. In The Return, Matar has created a testament of rare power—one that is as much about resilience as it is about sorrow, as much about love as it is about loss. Few books are as harrowing, or as profoundly humane.

A Final Note

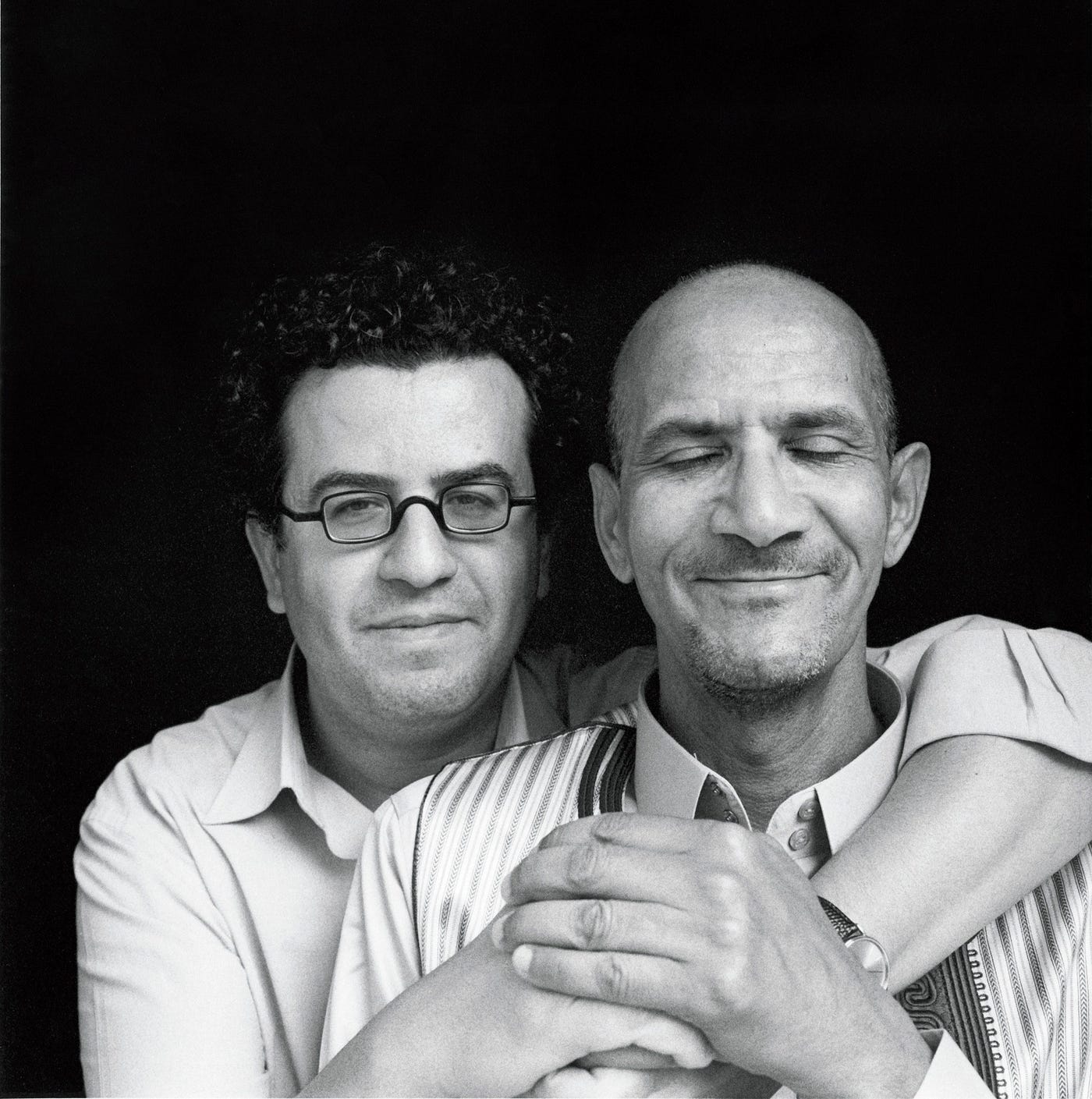

I leave you with this incredibly insightful interview, where Omid Memarian and Sarah Leah Whitson engage with Hisham Matar on literature—focusing on his latest novel, My Friends—as well as the Middle East, Palestine, Israel, and Libya.

Pour yourself a nice cup of coffee or tea, and enjoy the read!

Here’s a sneak peek:

Omid Memarian: How does your experience and the situation in Libya resonate with the ongoing plight of millions of Palestinians who have been in exile for decades, and with the current tragedy in Gaza, with over 40,000 people killed and nearly 2 million people displaced internally? How do you see the parallel parallels between these two experiences of displacement and loss?

Hisham Matar: What’s happening in Palestine is of a completely different order. It's the tragedy of our moment. The scale is unfathomable, and the numbers you mentioned are the numbers we know of. There's lots of people under the rubble that haven't been found yet. These numbers would be completely different if we were talking about another place where different norms of how you measure loss could be exercised. Whereas here is this moronic situation where everything is contested and everything is accused of being a lie.

It's also a moment that has exposed a lot about the region. Palestine has always done that. At this moment, it has really shown something quite dark and unpleasant about the region—and why the Arab Spring had so many enemies, not only in the individual countries where it sprung up, but from regional powers and international powers. Because if you were to have accountable and democratic societies, with accountable leaders, foreign powers wouldn't be able to control and marshal them in the way that they're being controlled and marshaled now.

But it's also exposed so much about what has been going on inside Israel over the past 25 years or more—how Israeli society has really changed. I've always found Zionism to be a deeply unjust project. But I'm also aware that Zionism itself has changed. These various politicians and pundits and the crew that are around them that make the public discourse in Israel have shifted public opinion to the right. There are reasonable people in Israel who disagree with what's happening, but they've become a shrinking minority.

The whole project about what Israel wants has also been exposed during this time. It has shown the extent to which it's willing to go, and what its language is. The language is fascinating—it's public, it's not a secret. It's all out there. I think it tells us a lot about what the new Israel is thinking.

But I would say also, the other thing that it has exposed is how impressive the Palestinians are—to try to survive under these conditions. To remain resilient, to remain committed to their ancestral rights, to their land, to their home, to their people, is very, very impressive. Like I've always told my African American friends, that I feel that in America, one of the things that is missing is a genuine celebration of African American resilience. The fact that they continue to write songs and write books. It's a cause to be proud of. If you're African American, you walk with your head held up high. I feel the same way about the Palestinians and what they have managed to endure so far.

Thank You for Reading

Reading and writing are, to me, the deepest forms of meditation.

I’m still finding my rhythm on Substack—balancing research, deadlines, and the chaos in between—but I’m grateful you’re here. I want this space to have a Sunday paper feel, a place to step back and reflect rather than add to the noise.

We don’t just read to know more; we read to see differently. I hope my writing sparks something for you. Let me know what you think—I’d love to hear from you.

With thanks,

Dilek

Thank you for making me want to read this book! Beautifully done as always!