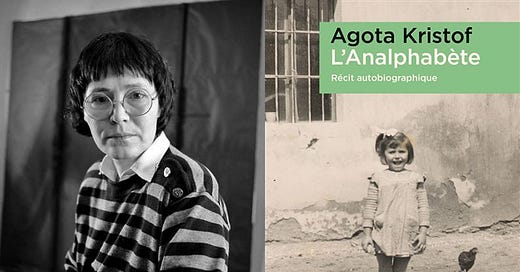

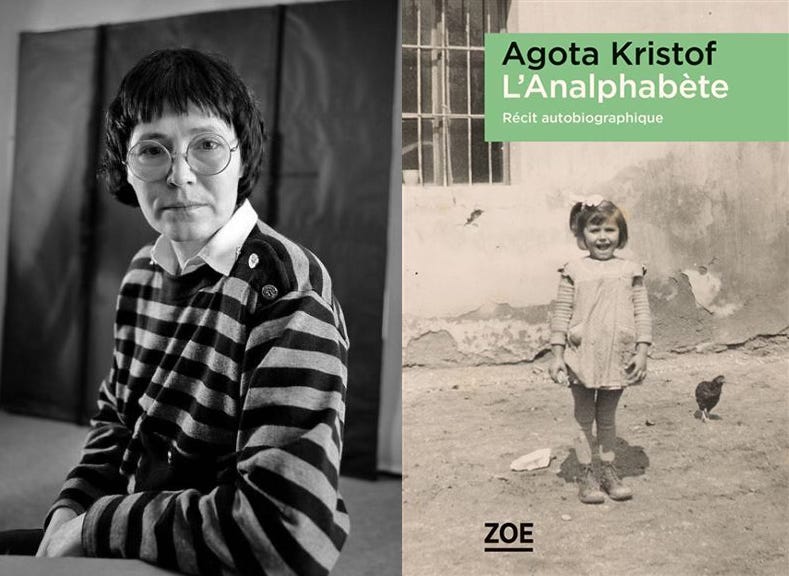

How Do You Write This Powerfully? Ágota Kristóf and the Trauma of Exile

On silence and survival—and the extraordinary literary force of Ágota Kristóf.

What would my life have been like if I hadn’t left my country? More difficult, poorer, I think, but also less lonely, less torn. Happy, maybe.

— Ágota Kristóf, L’Analphabète.

A Sudden Hunger to Reread

I don’t know what it is about the current state of global affairs—Oh wait, maybe it’s the three ongoing wars, the mass displacements, the endless exiles, all justified in the name of fighting terrorism. And all of us pretending that these people are going “somewhere” when, in truth, they’re hurled into a nowhere-land of exile—or simply into death.

Right? Maybe. Who knows.

But I’ve found myself with a powerful, almost physical urge to reread Ágota Kristóf’s L’Analphabète (The Illiterate in English, Okumaz Yazmaz in Turkish).

It’s a slim book—barely 40 pages—but it opens a window onto something massive. I’ve read Kristóf before with wild excitement, always gripped by the same question: How can someone write this powerfully—how?

This tiny autobiographical collection partly answers that question. And partly, it makes the mystery even more haunting.

Exile, Silence, and a New Language

When I first looked into her life, I learned that Kristóf fled Hungary at the age of 21. Her husband had taken part in the anti-Soviet uprising—what we now call the Hungarian Revolution—and they were forced to escape, eventually ending up in Switzerland.

She didn’t speak a word of French when she arrived. And she didn’t publish her first novel until she was 51.

What I hadn’t realized was how much effort she poured into learning French—a language she hadn’t even encountered until adulthood, in exile, while raising a baby.

To learn an entirely foreign language under those conditions and go on to write monumental literary works in it?

My God. Doesn’t that make the question even more bewildering?

How? Seriously—how?

The Violence Beneath the Surface

The trauma of language loss—of suddenly becoming “illiterate,” as the title suggests—layers itself on top of the trauma of displacement. And it’s all happening while she’s trying to survive, to mother, to carry on.

This, I think, is where the dark, stripped-back violence in Kristóf’s work comes from. It’s not decorative. It’s not stylized. It’s lived.

Her short novel Yesterday is a perfect example. The bleakness, the factory labor, the sense of slow suffocation—it all reads as heartbreakingly autobiographical. When you know what she endured, the book becomes even harder to look away from.

Forty Pages, a Thousand Reverberations

L’Analphabète offers a condensed yet piercing glimpse into Kristóf’s inner world. In just a few pages, you come away understanding not just her writing—but her.

And then there are the brief but luminous passages where she praises Thomas Bernhard. I lingered there, too. I loved those parts.

My admiration for her—already immense—only grew.

What Comes Next: The Trilogy

I’m looking forward to diving (or re-diving) into her other works, especially the legendary Notebook Trilogy (La trilogie des jumeaux), which includes:

Book I: Le grand cahier (The Notebook)

Book II: La preuve (The Proof)

Book III: Le troisième mensonge (The Third Lie)

If you haven’t read her, L’Analphabète is a stunning place to start—especially if you’ve already read The Notebook or Yesterday. The weight of her voice, once you know where it comes from, is unforgettable.

You become a writer by writing with patience and obstinacy, without ever losing faith in what you write. — Ágota Kristóf, L’Analphabète.

What a Woman, Truly—What a Woman

There are few writers whose lives and language are fused so completely, whose silences feel louder than their words. Ágota Kristóf is one of them.

And still, the question lingers:

How can someone write this powerfully—how?

A Desert to Cross: A Final Excerpt

It is here that the desert begins. A social desert, a cultural desert. After the exaltation of the days of revolution and escape, come silence, emptiness, nostalgia for the days when we felt we were participating in something important, even historic, homesickness, and the lack of family and friends.

We were waiting for something when we arrived here. We didn’t know what we were waiting for, but it was certainly not this: these days of dismal work, these silent evenings, this frozen life, without change, without surprise, without hope.

Materially speaking, we are a little better off than before. We have two rooms instead of one. We have enough coal and sufficient amounts of food. But compared to what we have lost, we are paying too high a price.

On the bus in the morning, the ticket-taker sits down next to me. In the morning it is always the same one, fat and jovial. He talks to me for the whole ride. I don’t understand him very well; I understand nevertheless that he wants to reassure me by explaining that the Swiss will never allow the Russians to enter the country. He says that I must not be afraid any longer, that I must no longer be sad, that now I am safe. I smile.

I can’t tell him that I’m not afraid of the Russians, and that if I’m sad, it’s more because I’m too safe at present, and because there is nothing else to do or to think about than the job, the factory, the shopping, the laundry, the meals, and nothing else to wait for but Sundays when I can sleep and dream a little longer about my country.

How can I explain to him, without hurting his feelings, and with the few French words I know, that his beautiful country is a desert for us, the refugees, a desert we must cross in order to arrive at what is called “integration,” “assimilation.”

— Ágota Kristóf, L’Analphabète.

Thank You for Reading!

And keep reading, cher lecteur/chère lectrice. Maybe pick up a book by Ágota Kristóf—or perhaps Hisham Matar.

Les livres ? Ce sont des médicaments.

Stay tender, stay aware, and take good care.

With gratitude,

Dilek