Mind the (Data) Gap

Scenes from the life of an economist navigating public finance consulting, municipal data gaps, and the politics of funding design.

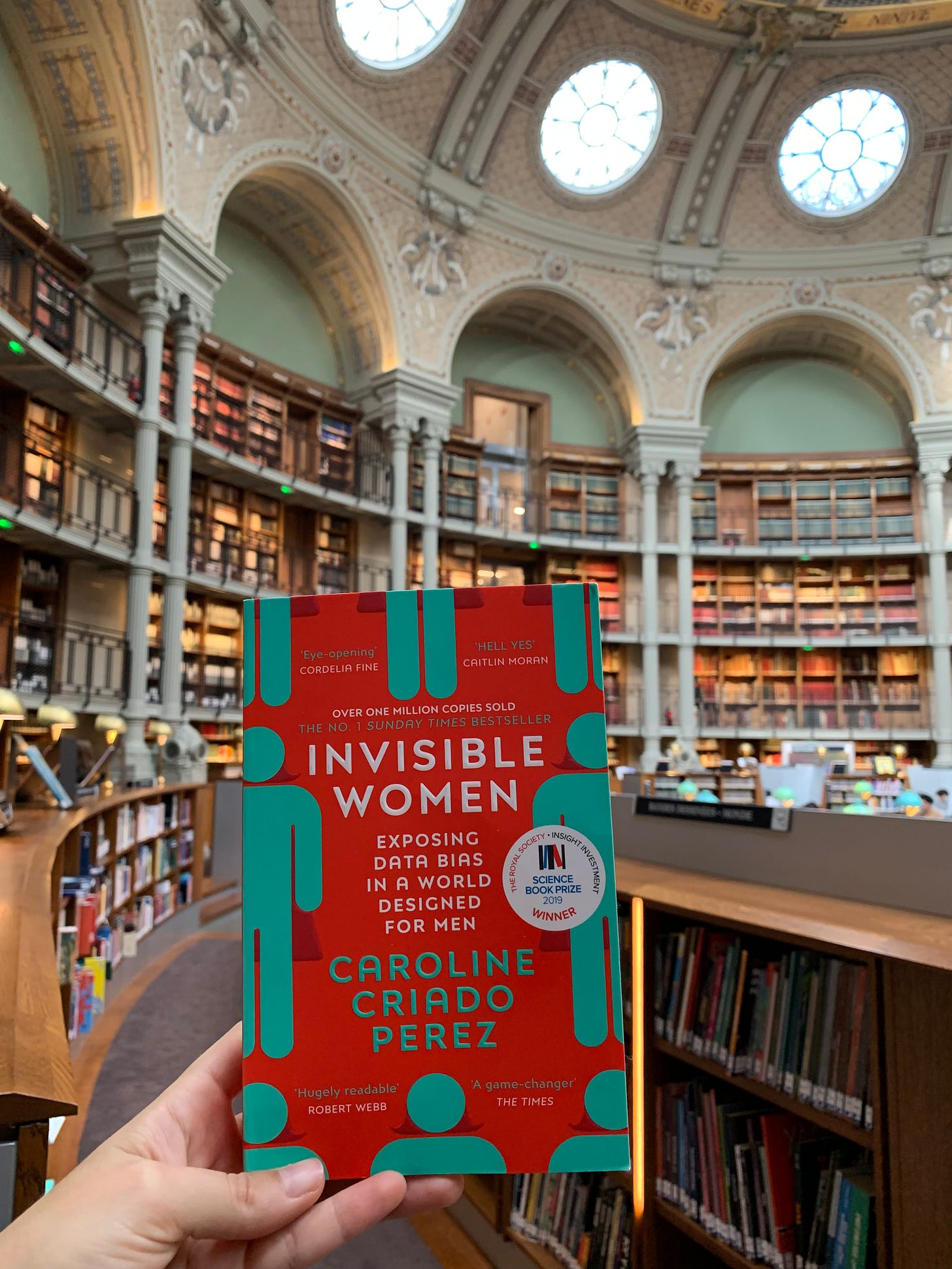

Recently, I had the privilege of giving multiple talks at Trinity College Dublin, engaging with graduate students, practitioners, and entrepreneurial public servants. I shared how our teams at the mayors’ offices of the City of Paris and the City of Montréal use inclusivity analytics to collect and disaggregate data by gender and other intersecting characteristics—including youth in need and immigrant communities. The goal of this work is simple but urgent: to support more equitable city planning and public service delivery.

Comme d’habitude, I gave concrete examples—covering topics like housing (or the lack of it), snow clearing, bike lane design, public lighting, and transportation infrastructure—to show how gender and inclusion shape urban design and everyday access.

Gender Mainstreaming in Paris

Gender mainstreaming is a strategic approach to achieving gender equality by embedding equity in the structures, services, and operations of city governance. The goal is to ensure that all individuals—women, men, and gender-diverse people—have the conditions, freedoms, and support to shape their lives according to their needs, roles, and aspirations.

In Paris, our subdivision supports city departments in implementing gender mainstreaming. We demonstrate how embedding gender considerations improves the fairness and effectiveness of city services. Gender mainstreaming isn’t about treating everyone the same—it’s about creating equity by recognizing differences and ensuring systems are responsive to them.

What Does Gender Mainstreaming Aim to Achieve?

Gender mainstreaming seeks a society where opportunities, responsibilities, and freedoms are shared equitably. Once achieved, equality becomes a foundational part of how cities function, not an afterthought. Importantly, women and men are no longer treated as homogenous groups—their differences in age, ethnicity, income, and social position are considered in planning and delivery.

Our team’s broader equality objectives in governance and city planning include:

Equal career opportunities across genders,

Fair distribution of paid and unpaid work, and wages that support independent living,

Gender balance in political representation and participation,

Challenging and transforming restrictive gender norms,

Equal personal freedoms and protections from violence and aggression.

Identifying the diverse users of public services—and understanding their distinct needs—enables city leaders to deliver better outcomes, align services with lived realities, and improve accuracy and success in planning.

The Five Principles of Gender Mainstreaming

All gender-mainstreaming activities in Paris are guided by five fundamental principles:

1. Gender-Sensitive Language

Communication must make women and men equally visible—including forms, documents, online content, posters, public messaging, and visuals.

Visual materials must be chosen carefully to reflect gender inclusion.

2. Gender-Specific Data Collection and Analysis

Data should be collected, analyzed, and presented by gender, and disaggregated further by age, income, ethnicity, education, etc., where possible.

A gender-specific baseline analysis must inform every decision.

We owe much of our approach to the pioneering work of the City of Vienna. Their frameworks and tools have been an inspiration, and we are grateful for their leadership. Key resources include:

Gender-sensitive statistics: Making life’s realities visible.

Data excellence in the Vienna City Administration: Gender statistics and data on equality.

3. Equal Access to and Use of Services

Services and products must be evaluated for how they affect women and men differently. Key questions:

Who uses the services?

Who are the clients and target groups?

Do women and men have different needs?

Are different circumstances (e.g., caregiving roles, mobility) reflected in planning?

Is information accessible to all groups?

Who benefits most—and who loses out if excluded?

Are service spaces gender-responsive (e.g., safe lighting, signage, accessibility)?

4. Equal Participation in Decision-Making

Targets are set for balanced gender representation at all decision-making levels.

These apply across project teams, advisory groups, commissions, and public events.

Workplaces should be structurally inclusive, accessible, and safe—including social spaces, archives, and signage.

5. Integration into Steering and Evaluation

Gender equity built into quality management systems and budgeting processes from the outset.

Gender-disaggregated data informs goal-setting, performance monitoring, and program design.

Regular evaluations include reviewing the gendered and intersectional impacts and making adaptive adjustments to strategies.

Equity-driven planning not only enhances program success but also boosts staff capacity, ensures cost effectiveness, and optimizes the utilization of public resources.

Gender Mainstreaming in Practice

Equality of women and men must manifest at multiple levels simultaneously: in politics, business, the labor market, public health and housing, education, law, and mobility. It also encompasses protection against violence in public and private spaces, as well as communal services like childcare, eldercare, and public transportation design.

Social Finance & Gender Budgeting

Gender budgeting is the fiscal instrument of gender mainstreaming. Its goal is to ensure that public budgets are allocated in a way that promotes gender equity. This is not about creating separate budgets, but about embedding equity into the existing budgeting process.

Key questions include:

Who benefits from financial resources and services?

How are services accessed and used?

Do resource allocations and distributions help reduce or reinforce gender disparities?

Key Considerations for Gender-Responsive Budgeting

What is the gender ratio in the target area or population?

How are expenditures distributed by gender?

Who uses the services or products in question?

Data Collection Guidelines

Begin with gender-disaggregated data, and where possible, further disaggregate by age, income, education level, ethnicity, and disability.

Collect data at a level of detail sufficient to inform equity-based decisions—for example, through traffic counts or targeted surveys.

Analytical questions to guide planning:

How will this initiative affect women and men differently?

Who currently benefits from this service or product?

Who is likely to be excluded or disadvantaged?

How can the initiative be adapted to better serve all genders?

How can services and/or products be designed to better reach and serve the actual target groups? How can priorities be set accordingly?

Vienna as a Leading Example

In 2005, the City of Vienna formally integrated gender budgeting into its administrative structure. With the 2006 budget, Austria became one of the first countries to include a dedicated chapter on gender budgeting in both its budget proposal and financial statements.

Unlike many approaches that focus on select budget lines, Vienna applied gender analysis to all budget items—embedding it systemically into fiscal governance.

Since 2009, this has also been a legal requirement under Article 13(3) of the Austrian Federal Constitution, which mandates gender equity in budgeting at ALL levels of government. I mean, tears, literal tears. 🥹

This model continues to inspire our work in the cities of Paris and Montréal. Our aim is to bring this level of ambition and institutional commitment to France and Canada.

Work and Education

Although legal frameworks ensure formal equality, women still face systemic discrimination in the labour market—from wage gaps (women earn, on average, 25% less than men1) to underrepresentation in leadership and male-dominated industries.

Vienna’s Model: Supporting Women in Technology and Research

The Vienna Business Agency offers targeted incentives for women-led or women-majority teams in tech and research projects. Grant programs prioritize gender equity at all levels—from team composition to project design.

Evaluation committees are gender-balanced, and funding criteria include a review of how gender is addressed in both the project and the organization. This approach is not only fair—it is strategic: inclusive teams produce more innovative, socially relevant solutions.

Public Space

Public Lighting

Women experience higher levels of harassment and perceived risk in public spaces, underscoring the need for gender-sensitive urban lighting. In our ongoing work for the City of Paris, our team draws inspiration from Vienna’s innovative approaches to this issue. For example:

Large parks—often celebrated for their scale—can also create conditions of insecurity. That’s why we’re currently evaluating lighting upgrades and safety improvements for both Montréal and Paris, in collaboration with their respective mayoral offices. These evaluations are based on city surveys and data that factor in gender and other intersectional characteristics.

🌃 Parc de la Villette (Paris)—Scale, Edges, and Uneven Use

Located in the 19th arrondissement, Parc de la Villette is one of Paris’s largest and most architecturally ambitious parks—home to cultural institutions like the Cité des Sciences, concert venues, and themed gardens. It’s vast, multi-zoned, and intersects with bike paths, canals, and major transit routes.

Lighting Challenges:

The park's peripheral zones and internal connectors are often poorly lit at night, especially outside event hours.

Footpaths and bicycle parking areas lack consistent visibility, creating shadowy pockets and limiting use after sunset.

Gendered Safety Considerations:

The sheer scale and openness of the park, combined with limited passive surveillance in some areas, can create a sense of exposure or discomfort, particularly for women walking alone at night.

Informal feedback from users and advocacy groups has highlighted safety concerns, especially in parts of the park further from active cultural hubs.

Potential Intervention:

Apply uniform, human-scale lighting along footpaths, especially near canal crossings, bike stands, and transit interfaces.

Integrate gender-sensitive design audits into future public works and programming—focusing on lighting, visibility, and spatial legibility.

Why It Matters: Even in a city celebrated for its public realm, parks like La Villette reveal how urban design can unintentionally exclude—and how lighting, when done right, can invite people back in.

🍁 Parc Jean-Drapeau (Montréal)—Visibility, Isolation, and Risk

Geographic Challenge: Located on Île Sainte-Hélène, Parc Jean-Drapeau is physically detached from the city’s dense residential areas. Access requires crossing bridges or tunnels, often by car, metro, or bike—which limits spontaneous or casual evening use.

Lighting Deficiencies:

Despite recent revitalizations, many trails, bike paths, and gathering areas remain unevenly lit.

Bicycle parking, event zones, and underpasses can be especially isolated and dim at night, increasing the perception—and reality—of risk, particularly for women and youth.

Gendered Impact:

The isolation amplifies vulnerability. What might feel like “tranquil urban nature” during the day can quickly become a deterrent space after sunset.

Women and marginalized users—especially those without access to private transport—are disproportionately excluded from evening access to this public space.

Opportunity for Change:

Clear, even, and targeted lighting of key infrastructure—especially paths, bicycle stands, and waiting areas.

Could be integrated into smart-city or climate-resilience strategies under Montréal’s urban equity goals.

Well-designed lighting benefits everyone—but especially non-motorized users like women, children, youth, and older adults. Gender-equitable lighting means rethinking priorities: it’s not just about lighting roads, but fully illuminating footpaths, waiting areas, and gathering spaces.

Our Implementation Principles

Our work is guided by the core principle of “see and be seen”—enhancing both actual safety and the individual sense of safety in public space. This is key to supporting gender-equitable mobility across the city.

Key implementation actions include:

Integrating gender mainstreaming into ongoing maintenance of existing public lighting systems.

Launching park-wide assessments to evaluate current lighting conditions, especially in underutilized or low-visibility areas.

Developing a catalogue and open data resource of targeted interventions for critical pedestrian crossings, in collaboration with municipal traffic planning and operations teams.

These measures aren’t just technical fixes—they’re a commitment to building cities that truly see and serve everyone who moves through them.

Because when our streets and systems reflect the realities of everyone who uses them, we don’t just design better cities—we build fairer futures.

This is how we move from disaggregated data to reimagined public space—one light, one street, one policy at a time ✌🏾🫡

Appendix: Gender-Sensitive Urban Design in Action (Vienna)

The City of Vienna has long led by example in applying gender-focused data to real projects. Below is an example of how such data influenced lighting improvements tied to a tram extension:

Project: Extension of Tram, Subway, or Train Line

Construction Phase 1 – New Lighting System

Lighting upgraded in adjacent parks, sidewalk areas, and pedestrian protection paths. The planning process accounted for local site conditions, ensuring improved coverage through stronger, more targeted bulbs. As a result, lighting levels on-site now exceed standard intensity requirements.

Phase 2 – Station Area Illumination in Industrial Zones

Lighting design considered structural elements of the subway, particularly areas where overhead supports cast shadows. To eliminate “anxiety zones” —dark, obstructed spaces beneath the subway—additional lamps were installed to ensure continuous and even visibility along walking routes.

Construction Phase 3 – School Route Illumination

Pedestrian routes to nearby schools prioritized. Special attention given to ensuring that surrounding pedestrian crossings are sufficiently and safely lit for children and caregivers during transit hours.

Thank You for Reading!

No, I haven’t forgotten you, cher reader. I’ve just been swamped—juggling journal deadlines, teaching, and all the usual yaddi yaddi yadda.

Still, I want this space to be less about constant takes and more about thoughtful reflection—and, of course, a bit of me venting, comme d’habitude.

I’d love to hear your thoughts—write to me anytime. And bien sûr, thank you for being here.

With gratitude,

Dilek

🇨🇦 Canada

National Average: According to the Canadian Women's Foundation, women working full-time, full-year earn approximately 75 cents for every dollar earned by men, reflecting a 25% gender pay gap. canadianwomen.org

Ontario Specific: The Pay Equity Office of Ontario reports that female employees earned $0.75 for every dollar earned by men in 2020, indicating a 25% wage gap. payequity.gov.on.ca

🇫🇷 France

Paris: Data from Apur (Atelier Parisien d'Urbanisme) indicates that the average net hourly wage for Parisian women is €22, which is 21% lower than that of Parisian men, who earn €27.80 per hour. apur.org

National Average: In the private sector across France, women earn, on average, 23.5% less than men. However, when adjusting for factors like working hours and job positions, the gap reduces to 4% for equivalent roles and hours worked. mondediplo.com